Board Game: Endgame

Today I want to look into win conditions and the end game of various board games. I’m hoping to uncover some insight to apply to Elemancer, because like Stephen King I’m struggling to create a proper conclusion. For reference I’ll restate the impetus for Elemancer: a deckbuilding game with RPG aspects including PvE combat, map movement, and resource management.

Increasing Resource

Often represented by ‘victory points’ this is a resource that ticks up as the game goes on. This is the go-to win condition of many games, rewarding players for accomplishing favorable goals within the game. Sometimes that goal is tautological: gain victory points. However, I’ve found while writing that in many cases these resources must be limited in some way so that the game actually ends.

Dominion: Prosperity

Dominion is interesting in that the victory cards are themselves a limited resource. In later expansions (beginning with Prosperity, I believe) there are cards that generate victory point chips that aren’t cards in your deck. “Greening” and the limited number of high VP cards (typically Provinces) means there is a growing tension as opponents start to gain a larger share of these cards. This puts pressure on players to end the game. Another interesting aspect of Dominion is that victory cards go into your deck and dilute it, which isn’t something you want to do too early. In games with an unbound, increasing resource like VP the winner is determined relativistically, so ending the game earlier versus later depends on how well you’re doing at the time. However, with certain expansions there are kingdoms that lend themselves to unbounded VP acquisition.

Limited Increasing Resource

I realized this should be its own category, and could encompass Dominion in some ways. In this case the resource is hard capped, which signals the end of the game as it depletes. Such resources are transferred from a limited pool to the players. The share that each player gets varies, which is why I view it as an increasing resource that (often) directly represents the player’s standing in the game.

Dominion

Base Dominion is more straightforward in that what you see is basically what you get. Barring adding Curse cards to your opponents’ decks (and the variable amount of VP on Gardens cards), the total pool of VP is limited in each game based on the Estate/Duchy/Province piles. In a 2-player game it’s much easier to tell who has more Province cards, and you’re likely in good shape if you can get the simple majority of 5 Provinces. Again, this is a case where the victory cards are essentially being transferred from the Kingdom to the players’ decks.

Ascension

Ascension uses Honor tokens, which were a big inspiration for Gems in Elemancer. Of course, this is another case where the total pool of VP is bounded, similar to Dominion. This also a way of forcibly ending the game, preventing it from extending indefinitely. Game length can vary based on how efficiently players siphon from this shared pool.

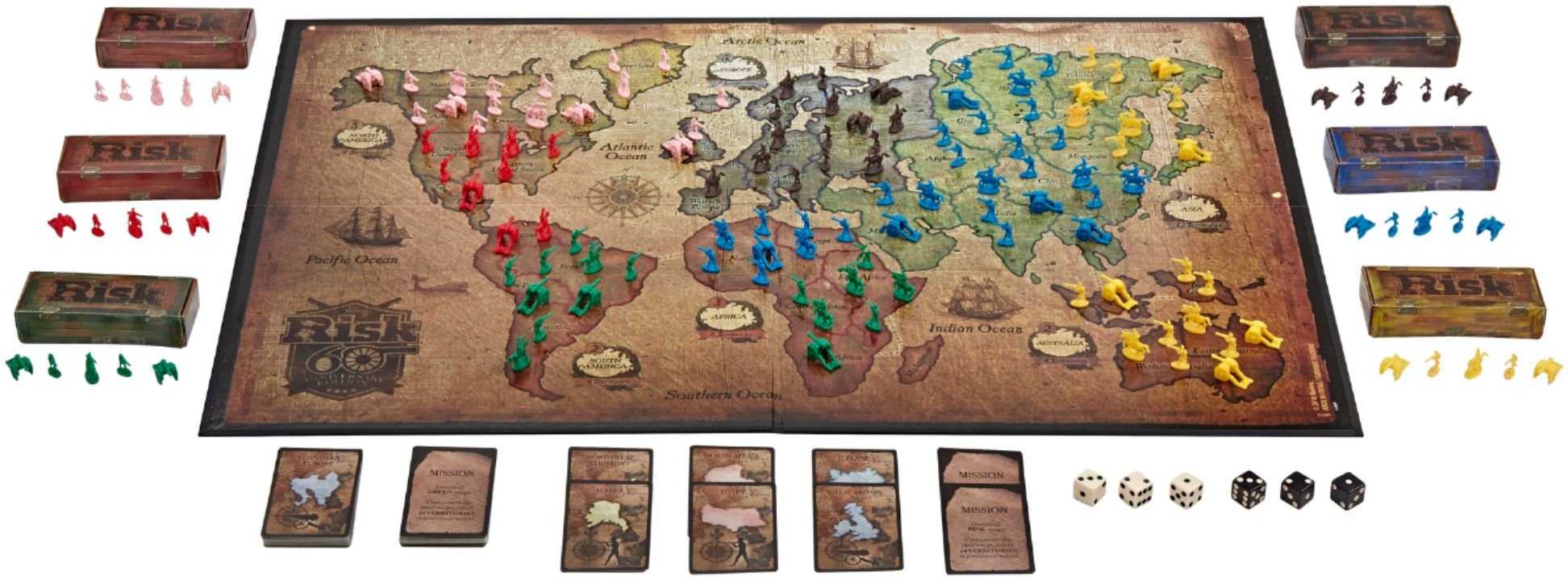

Risk

Risk is the classic game of world domination, and the win condition is just that: conquer the world. Filled with big swings and lots of dice, all players are fighting for the same resource: territories. As such, it can be simple to determine who is ahead at any one point of the game. More armies, better distribution, and a bit of luck will gain you an advantage, but to win the game you need to conquer your opponents’ territories. It’s as simple as that. The addition of Secret Missions (I’ll admit I’ve never used them) gives you a separate condition to declare victory, but base Risk is a straightforward fight.

Decreasing Resource

Some examples of decreasing resources include life totals and turn timers. Both impose a hard cap on the game length in some way, presuming that there’s a way to deplete the pool as the game moves forward. I ran into a bit of an issue with this in my early card game designs, where players had a certain amount of life but the games varied in length due to inconsistent damage or strong healing effects.

Star Realms

Star Realms uses Authority, which can increase and decrease throughout the game. The main interaction in this game is directly attacking your opponents and their bases, so from turn-to-turn you are inching towards the end of the game. Different synergies can accomplish this to greater effect or even outlast attacks (to some degree). The unbounded upper limit of Authority makes ‘over-healing’ strategies possible, though the game appears to be balanced in such a way that the damage far outpaces healing. This is a subtle balancing decision that may not be obvious at first blush, but an important factor that allows the games to end in a reasonable amount of time.

Imperial Settlers

Imperial Settlers is one of my favorite asymmetrical games, and is played over the course of 5 rounds. Within that time you have access to both faction and common cards that allow you to build locations and acquire resources. It is moreso a city-builder than a deck-builder, but it is closer to Race for the Galaxy in that cards become your locations. Each faction excels in different areas, and the faction deck gives you access to different synergies and provides a separate balance for each faction. The winner is determined by victory points, and each faction has its own way to gain extra VP outside of buildings.

Stone Age

Stone Age is one of my go-to games. The end game itself is signaled by the depletion of either the Civilization cards or Building tiles, each of which is hard-capped. The winner is the one who has the most victory points, which is not directly related to the lion’s share of Civilization cards or Building tiles, as there are other factors that can increase victory points. This is a great example of a game with variable game length depending on how you and opponents choose to play. I suppose there’s a reason it’s a mainstay for my friends and I, there is a lot of player agency and variation within each game.

Race for the Galaxy

Race for the Galaxy ends after you have 12 cards in your tableau or the predetermined amount of VP runs dry. So throughout the game you need to balance generating resources (in this case just cards in-hand) and inching towards the end condition. While victory points determine who wins, the game typically ends when you fill your tableau with worlds and developments. This creates an interesting tension that is face-up to the players. You can see when your opponent is in range of ending the game, which may affect your decisions.

Carcassonne

Carcassonne has increasing victory points with unknown potential limited by the available tiles. Like Stone Age, the end condition is separate from what determines who wins. The stack of tiles is effectively a turn timer. In person, it can be difficult to tell who is ahead at any one point unless you’re constantly recalculating everyone’s current point totals.

Risk: 2210 AD

Risk 2210 AD is a Risk variant set in the future where you can conquer water and moon territories. While others may prefer the simplistic nature of base Risk, 2210 adds action cards and specialized units with different abilities, as well as an energy economy. You still have dice-based combat, but the game is limited to 5 turns. In that time, you will not likely conquer every territory, but the winner is determined relativistically through accumulation of colony influence.

7 Wonders

7 Wonders is played over three Ages, and the winner is determined by victory points accumulated in that time. That is a vast oversimplification of the game, but the limited number of turns add an extra axis to the resource management within the game. Each player has their own faction with specific advantages. Combined with a shifting selection of cards available each Age and each game, this increases replayability and variance between and within games.

Meet a Condition

This is basically a catch-all category, but I’ll go into the specific conditions to see how they differ.

Settlers of Catan

Settlers of Catan falls into this category, even though it does use victory points technically. The difference is that you need a specific number of VP to win that is not taken from a shared/capped pool. You need to meet some number of conditions that total 10 VP. You can achieve this goal in a number of different ways, which helps the replayability of the game.

Betrayal at House on the Hill

Betrayal at House on the Hill is another game for which I have a less favorable opinion than many other gamers, though I will admit it can lead to some fun experiences. My issue is the variance is too high and I’ve played the same Haunts multiple times while others I’ve never encountered. As for the win condition, it depends on the Haunt itself. Sometimes they have a turn limit, but victory for the heroes often requires gathering things and making successful die rolls while victory for the traitor often requires eliminating the heroes. Unlike some other games, if you run out of room tiles in this game there is no penalty, though to not hit a Haunt in that time would be pretty impressive. Player stats could be considered a limited resource in the game, but you can’t die before the Haunt starts so I wouldn’t necessarily consider it a game with a decreasing resource. Especially since so many Haunts have a laundry list of tasks for you to complete in order to win.

Pandemic: On the Brink

Pandemic in my opinion feels unique because it feels more like a game of staving off loss conditions. Of course, the ultimate loss condition is running out of time, but the victory condition is to research a cure for each disease. As you tick each one off you can feel the game approaching its conclusion, but as the game goes on the tension is constantly increasing. It can be stressful, and there’s no shame in losing a few times at higher difficulty. Managing outbreaks, treating disease, and finding a cure shift in priority from turn-to-turn.

Dead of Winter

Dead of Winter is a (mostly) co-operative board game involving resource management, character abilities, dice rolling, and a lot of killing zombies. The victory condition depends on the main mission, but even if the players achieve that condition, you actually win if you also meet your hidden agenda. This can allow the introduction of traitor agendas if the play group is into it. Most missions have a hard turn limit, but victory itself is typically accumulating resources such as items or zombie heads (kills). Like Pandemic, there are a number of different loss conditions that you have to manage while trying to also actively win.

Monty Python Fluxx

Fluxx is a fast-paced game of constantly shifting rules. I have the Monty Python-flavored Fluxx, and it is as chaotic as the Holy Grail. Very fitting. In this game, win conditions have an entire card type dedicated to them (Goals), and players all see the face-up requirements. But of course, players can replace that at any time with another set of conditions, depending on cards in-hand. Victory hinges on having a certain set of thematically-linked Keepers (good permanents) and (in some expansions) having no Creepers (bad permanents in most cases). Game length varies wildly, but players have the agency to change the Goal and play particular Keepers, unless they must play their entire hand each turn.

Pokémon Master Trainer

Pokémon Master Trainer is a beloved but flawed game. I disliked a lot of aspects to the game such as forced trading and (importantly/ironically) the victory condition. The disconnect from the main series video games also spurred me to ‘improve’ the rules and mechanics to make a much more time-consuming adventure/experience. But other aspects were very fun, for example uncovering different Pokémon and specific die rolls for capture. There are some simple requirements to reach the Elite Four, including traversing the board and acquiring just enough Pokémon. Winning itself often feels unsatisfying and abrupt, unrelated to the core tenet of the early Pokémon franchise: “gotta catch ‘em all.” This rubbed me the wrong way, because all you needed to do was get lucky on the attack roll, hit an easier Elite Four member, and accumulate more of the good attack bonus cards (+5/+4) to get you over the threshold. It helps to have a strong Pokémon with an evolutionary bonus, but you don’t technically need to catch a bunch of Pokémon to win. In my updated rules, among other things players have to beat each Elite Four member in order, which means the attack bonuses get cycled more often. This was a bit excessive, but is definitely closer to the video game experience. I also introduced gyms and type-based tiebreakers. The Gen 1 Master Trainer game is definitely a good example of what not to do to end the game.

So after all this, what is the takeaway? First, there are not many games without a built-in limit of some sort. Often something becomes depleted and this triggers the end of the game, be it time or VP chips or cards. Cooperative games in particular often have turn limits, with the notable exception of Pandemic which has multiple imminent loss conditions. That said, I’ve definitely focused on a particular subset of board games, namely ones that I’ve played multiple times and (mostly) enjoy. Elemancer needs a way to signal the end of the game is imminent. I’ve been looking to implement a multi-part quest to give players direction throughout the game. It’s a bit heavy-handed but the first implementation of an endgame was an unbounded VP system, and that was both unsustainable and likely abusable. Of course I still have an issue of determining who actually wins the game.

A faceoff between players or a damage check of some sort requires very careful balancing of each Element. It’s doable, but restricts the power trip aspect reserved for a purely PvE game. Alternatively, there could be a final boss associated with each Tier 3 zone or each Element. This would allow for some Elemental builds to have a higher max or expected damage, but still be equally difficult. But even then, how should you determine who wins? I’ve moved away from a VP system that rewards players for fighting monsters, but I think reintroducing VP at the end of the game to represent relative standing could be acceptable.

What about an Arena with a number of stipulations/bonuses to attenuate the damage check? Each Tier 3 zone would have an associated Arena, then one would be randomly selected. That is in some ways an uninteresting coin flip, leaving too much up to fate and hoping you get a favorable Element. Depending on how deep I go into this Arena mechanic, there could be 3-5 static Arenas that grant different bonuses depending on what Elements are played (or not played) by each player in the final showdown. Winner is the one with the highest damage, which will be attenuated by the effects of the Arena. The Arena bonuses/penalties are an extra knob that can be adjusted to balance the Elements against each other, though some Arenas will likely be favorable to particular strategies.

Hopefully you’ve found this piece as enlightening as I have. I certainly have more work ahead of me, but this has been a fruitful dive into signaling the end of the game and determining a winner. As satisfying as the journey of a board game is, it is important not to leave a sour taste in players’ mouths at the final hurdle.